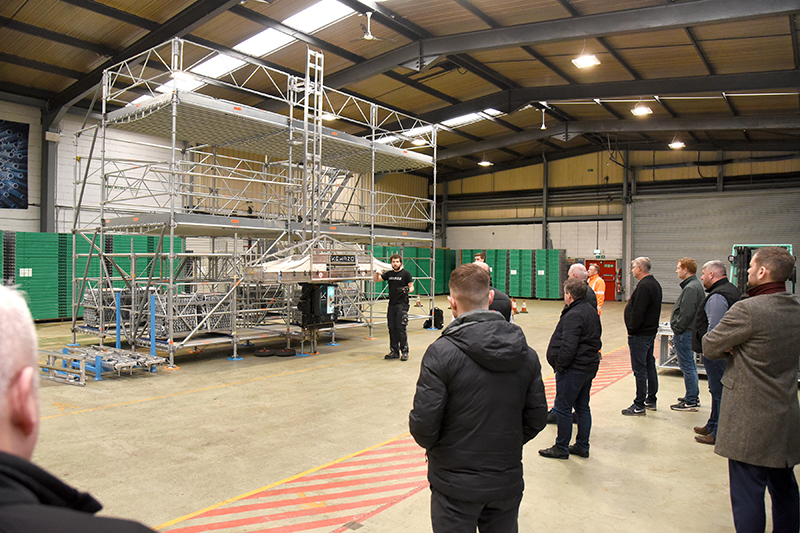

KEWAZO has praised the desire of the Scottish scaffolding sector to protect its workforce after showcasing its LIFTBOT robotic hoist innovation to leading industry members at a recent event hosted at StepUp Scaffold’s UK headquarters in Govan, Glasgow.

The German technology company has ambitions of increasing productivity and safety within the construction sector through digitisation and robotics, with its battery-powered LIFTBOT solution described as having the ability to save up to 70% in labour costs and boost working conditions.

The system has a lift capacity of up to 100kg and utilises one-touch technology that automatically sends materials to the determined scaffold level. Once unloaded, it autonomously returns to the ground location. The firm explained this cuts down the need for seven to eight labourers to just three.

Featuring data tracking software, project information is delivered in real-time to KEWAZO to be presented back to the user, in order to identify areas where project planning and cost efficiencies can be improved upon.

The technology has already been used on a number of high-profile projects across the globe, including in downtown Boston where local newspapers reported how it could signal an autonomous future for the construction sector. With labour costs high in the city, one scaffolding contractor was able to step away from its use of ropes and pulleys and utilise LIFTBOT to carry materials up and down an 11-storey building.

Dublin also had success with the technology on a city centre project, where it was installed on top of a pedestrian gantry which allowed people to walk around the vicinity without obstructions.

“In city centres it’s great because it has such a small footprint,” Simon Espinosa, sales manager at KEWAZO told Project Scotland. “In the UK you have quite small pedestrian walkways, so streets end up having to be closed to get material up (when manually lifted or using machinery with wires).”

Simon and his colleague, Alex Glatz, have been touring Europe presenting live demonstrations of LIFTBOT. Questions were aplenty at the Glasgow stop, with many focusing on health and safety and how much the technology can lessen the physical demands of their workforce.

“I’m glad those in attendance had so many questions and they cared about their scaffolders,” Simon added. “Something we really like about working in the UK is that safety standards are very high and that is why the adoption of LIFTBOT is imminent.”

StepUp has been a keen follower of the LIFTBOT since it came across KEWAZO at a scaffolding convention four years ago.

Marking the first collaboration between the two, StepUp volunteered its yard and materials for the live demonstration.

“Can three guys really build it? Put three guys on the job,” Simon continued. “Can it reduce my schedule? Put the same guys on the job with the LIFTBOT and see what happens to your schedule. Can the battery really last a whole shift? Try it out. That’s the whole point of the pilot – people don’t believe that LIFTBOT works as it does. Once they try it, they will.”

Explaining that KEWAZO doesn’t utilise distributors, Simon revealed that the firm wants to maximise dialogue with clients to ensure that it can adapt the LIFTBOT and hone it to the sector’s needs.

Released four years ago, alterations made include new baskets that can be turned into the scaffold at the desired level suited to scaffold frames used in Germany and North America and a basket for bulkier materials was also rolled out.

“This was all based on the needs of the scaffolding companies,” Simon explained. “We have designed everything very modular, so you can change one part and keep everything else.”

Sensors have also been implemented to alert users to potential risks such as overloading, doors being left open, as well as a shut-down sensor should the track be obstructed.

“Taking away human error was always important for us,” he continued. “As a scaffolder once said, ‘it doesn’t allow you to do something you’re not supposed to’ and that’s what we thought about. How can we reduce human errors? When you’re working with machines it’s usually not an error with the machine, it’s a human.”