A new report into Scotland’s 20-minute neighbourhoods has revealed several findings about the scale and type of developments needed to deliver such communities.

The 20-Minute Neighbourhoods for Scotland insight report from planning and development consultancy, Lichfields, analyses plans for places designed and built specifically to allow residents to meet their daily requirements within 20 minutes of their home.

It notes that the features of these neighbourhoods include a mix of safe pathways and cycle routes, doorstep health facilities and services, local schools, parks and open spaces, and affordable housing. The report adds that they also feature focus points for employment through the creation of jobs in construction, leisure, and retail.

The report says the Scottish Government is ‘committed’ to delivering 20-minute neighbourhoods, which are ‘gaining traction’ among the nation’s planning and policy decision makers. It also identifies the need for far more balance between development types and the needs of local people.

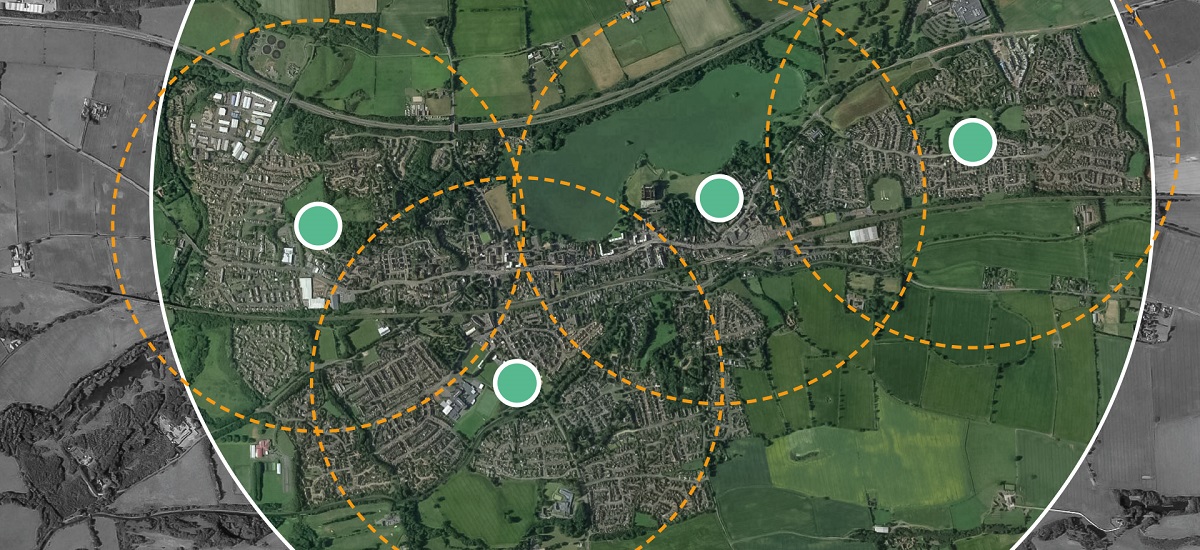

Linlithgow in West Lothian is showcased as an example of the type of 20-minute neighbourhood that can work well. There, people are able to reach local schools and access retail amenities on foot within 10-minutes. The majority of residential housing is also within 800 metres of a non-denominational primary school.

The report says that 100 people are needed per hectare to best support a good bus service, while 6,000 people living within 10-minutes are able to support town centres, and 24,000 people within 10-minutes are similarly required for a good district centre.

Greenfield sites on the edges of existing towns can help, the report added. It explained that these contribute ‘significantly’ to and being part of flourishing 20-minute neighbourhoods. If they are of a suitable size, large releases can in themselves become neighbourhoods. However, rural areas comprise communities with geographies that are different to the urban setting and an alternative approach may well be required, the report says.

In its analysis, Lichfields predicts that planning for 100 people per hectare within a five-minute walk to a bus stop and between 30 people and 90 people per hectare in a ten-minute walk of a local facilities, delivers the best balance if a place is to work as a 20-minute neighbourhood. It found that 46 units per hectare is the about the right starting point to support a good level of local facilities and bus services.

While a beneficial concept, the report reveals that more practical guidance is needed if Scotland’s quest for 20-minute neighbourhoods is to be better understood and delivered.

(Image credit: James Robinson)

Nicola Woodward, senior director and head of Lichfields Edinburgh office, said, “This research lifts the lid on the current situation, offering some much-needed insight into the idea of 20-minute neighbourhoods, which have gained traction among Scottish Government in recent times, particularly in the wake of Covid lockdown. It adds meat to the bone, revealing that it is density of people and not the number of houses that make the most sustainable communities.

“It also illustrates what an effective 20-minute neighbourhood can look like. Places like Linlithgow are 20-minute neighbourhoods built up over time but new developments either on their own or as part of established places can also be 20-minute neighbourhoods. It is important to look at developments on an individual basis if communities are to become sustainable and it is important not to be prejudiced against new places in greenfield locations.”

The report comes as the Scottish Government sets out how Scotland’s future towns and cities will be planned and designed in its latest National Planning Framework (NPF4).

Nicola added, “Where and how we choose to live our lives has a direct impact on our health and well-being, perhaps even more so than in these challenging times.

“Government has to recognise that producing carefully thought out and dynamic walkable neighbourhoods, connected through a mix of land-uses, housing types and access to quality public transport, can deliver long term.

“New homes is an emotive issue at the best of times and balance between ambition and reality can be hard to reach. However, in the clamour to build the housing we need, it remains as important as ever to strive to improve, innovate and think beyond the traditional and conventional. So, it’s only natural to want to see safe, inclusive and imaginative new neighbourhoods coming through that deliver legacy and a real sense of community.”