A formwork method utilising a system likened to the classic Pin Art toy is playing a key part in a new vaulted floor system which could see 60% less embodied carbon in builds.

Developed by the UKRI-funded Automating Concrete Construction (ACORN) – a partnership between the University of Bath, University of Dundee and University of Cambridge – the system uses 75% less concrete than a traditional flat slab floor.

Most building floors currently use thick, flat slabs of solid concrete – which rely on the bending strength of concrete to support loads, and with concrete ‘not being very good’ at resisting tension induced by bending, the floors require steel reinforcement.

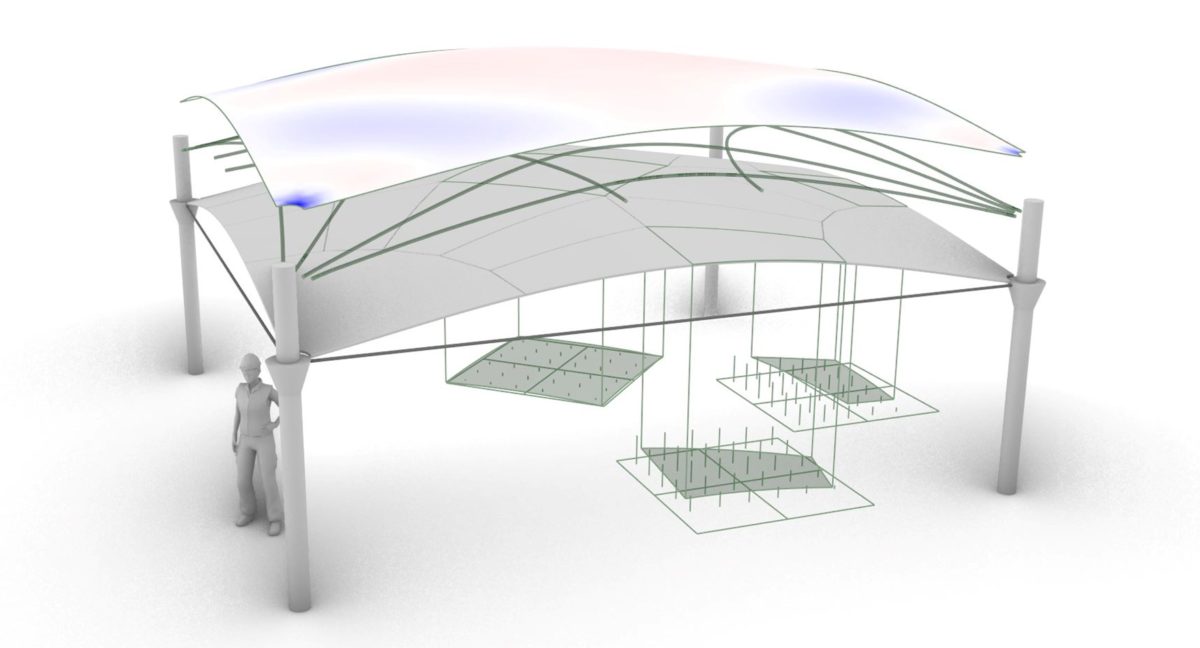

ACORN’s approach seeks to build on the ability of concrete to resist compression by putting the material only where it is needed – leading to less use of concrete, through the creation of the curved, vault-shaped structure that is covered by standard raised floor panels to create a level surface.

Paul Shepherd, reader in the University of Bath’s department of architecture & civil engineering and principal investigator at ACORN, told Project Scotland that traditional formwork methods could be used on the system – but, ultimately, it would require the use of materials such as polystyrene and be ‘massively’ labour intensive, which wouldn’t fit into their vision of a fast, scalable and carbon-efficient system.

“What we’re really keen to do is use a mass-production-type factory,” he said. “All our decisions have been based on what would work at scale; if you’re going to change the world, it’s got to be a process that you can constantly churn out.”

The formwork method used for the system is based on the Danish Adapa model, which was developed to make facades rather than structural elements of buildings. A grid of computer-controlled pins drop down to make the required bottom shape – in the same way a Pin Art toy would outline a hand pressed onto it.

A textile sheet is then placed over the top alongside a timber frame, with a robot spraying a mix of concrete and chuck glass fibres to ensure reinforcement is distributed across the entire area. “Even though we’ve worked out the shape to maximise compression there are multiple load cases and there’s always going to be some tension knocking about,” Paul added. “We need a bit of reinforcement there.”

The group recently showcased the vaulted floor at a media event at the University of Cambridge. Although Paul said he believes it will one day become the norm, given climate pledges and increasing prices, he said that the system is not yet ready to be commercialised – mainly due to the pandemic and supply chain shortages hindering work.

“This is a research project, and with research you answer some questions and it opens up more,” he explained, before telling how they have applied for another round of competitive funding – in what he believes will be the final point of the project before commercialisation. “Our team proved to people that it is possible at scale, but things like, for example, performance in fire (must be shown) – we are confident there is solution to that, and the current solution is to throw concrete at that, and that’s not where we want to go; we’re confident that there are solutions, but we haven’t had a chance to do the research to develop a system and demonstrate it to a level required by an insurance firm or building owner.”

Backing for the project has been strong, with ACORN having 12 industry partners – ranging from architects to engineer consultants and contractors – who were formally engaged in the initiative three years ago prior to it receiving any funding, as well as an additional 15 formal affiliates who came onboard midway through the project.

Paul said the level of interest in recent weeks since the demonstration has been ‘phenomenal’. He admits that five or ten years ago people might have thought it was too complicated, but the potential to save a quarter of the concrete is hugely appealing in the modern world.

“The research is the end of a three-year project, which was funded by the UKRI, under a programme called Transforming Construction, and I think that was a massive injection into research under both industry and academia to transform construction,” he added.