THIS year’s Royal Society of Edinburgh’s summer events programme Curious featured a number of thought-provoking discussions on a range of topics, including some which were particularly pertinent to the future of the construction industry.

Karen Anderson FRSE, architect, hirta, chaired an event called Making Space to Thrive, which examined the links between the built environment and health and wellbeing. The talk focused on more inclusive and healthy design.

Speaking ahead of the event, Karen told Project Scotland that architects and planners, by default, address the challenges of their times. Now that means, first and foremost, climate change; designing in the context of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic; considering social inclusion; and with more emphasis on mental health and wellbeing.

Of vital importance is strengthening social and community networks in a world where people are increasingly using virtual space, and with the demise of the high street and many of the structures which we understood as our social connectors in the past.

“In the past architects were more inclined to focus on creating buildings – architectural space that is both inspiring and functional,” she explained. “Now we must think about much wider social challenges and fundamentally the climate and resource aspects of everything we do. Architectural practice is becoming wider.”

Behavioural change associated with the pandemic has been needed and widely accepted since the start of the initial lockdown period. Karen said the question is what are the long-term implications of this for the built environment?

“Certainly, some of our companies and other organisations are thinking about how they will work in the future in the context of a more ‘blended’ working economy,” she added.

“I think that will open up a challenge in terms of the amount of office and commercial space that we have. Already we are talking about how some of that might be converted to housing. The question is how do you make sure these are really good homes, facilities and places that people actually want to live in as opposed to just fitting out an office to provide a flat? That doesn’t solve the problem; that just creates a new problem to kick down the line.

“New checks and balances are required – new measures of higher quality for living.

“There have definitely been changes in awareness as a result of the pandemic. People are more aware of their space; they’re aware of the importance of the outdoors – and at scale. It’s not just your balcony or garden; it’s your connection to greenspace at a neighbourhood, city, or national level.”

Karen said there’s always been an understanding of the importance of architecture and design and how it affects people. “It’s been used to small ‘p’ political ends in the past – for good, in say, the best social housing, and new health buildings,” she explained.

“It’s about society putting architecture to work in terms of what it values. Right now we need to think about sustainable buildings and places that are great to be in and feel good for the long term.

“How you design the environment affects your psychology; your wellbeing. Is there fresh air in the room? Is it feeling the right temperature? Is the sun coming in instead of having north facing small windows? Then there’s the wider issue of what is it built of. Is it a sustainable material? Is it something that really feels ethically right to build and be in?

“There are countries that value the social aspect of architecture and design highly because society values that.

“For example Scotland has tended to have better social housing space standards than those south of the border. It’s a question of building on that. We can build better, more resilient and accommodating buildings.

“It’s a question of getting our procurement to truly prioritise design for the long term; rather than immediate, short-term costs. Too often we design to an ‘optimistic’ budget and timescale.

“We have no real mechanism to look at collateral and longer term costs as we live in an GDP-based economically driven society. As such, only by legislation does quality in construction in the mainstream get better, more sustainable. We introduce better building regulations to get better performing buildings. We’ve introduced planning policy to try and get better places.”

Karen highlighted the Secured by Design initiative, which focuses on the security of buildings and their surroundings – but noted we don’t put the same ‘filter’ on how a building works from a social and wellbeing point of view.

“The best clients and architects do that by default but it’s not as in place as it might be,” she added. “I think we need to move to a position where we examine all development through that lens.”

Another discussion on the Curious programme centred on the challenge Covid-19 presented to mechanical engineers.

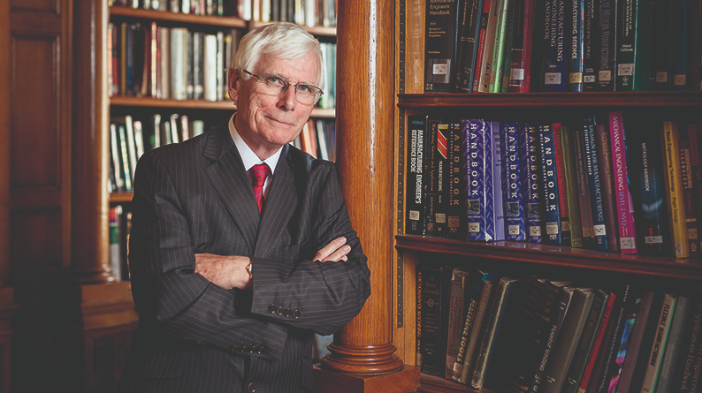

The talk was chaired by Professor Joe McGeough FRSE FREng FIMechE, who played a leading role in a taskforce set up by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers early on in the pandemic to provide information and guidance to the public, industry, and government bodies, on how to combat the virus. They produced a manual which considered how to make buildings safer by ventilation and control of air quality.

Joe and his colleagues considered a wide range of settings including hospitals, care homes, aircraft/airports, and even car washes.

“My colleagues are unsung heroes, providing practical solutions to very practical problems,” Joe told Project Scotland.

“When the new Nightingale hospitals were being set up, we were asked to provide some sort of evidence or guidance as to how post-Covid hospitals could be made safe. We advised on improving ventilation and air filtration and looked at how we could put in place remote patient monitoring to reduce risk to staff and make wards as flexible as possible.

“We considered the planning of car parks, how taxis could be made safe, and under what circumstances could handling tools be made safe.

“One of the things we were asked to do on the taskforce was consider the design of buildings for the future to make them Covid-friendly. A large part of that comes with ventilation, air quality.

“Ventilation is obviously very important. There is now relatively low-cost machinery available that will kill the virus using ultraviolet.

“Mechanical engineers won’t be able to do this on their own; they’ll have to work with architects who design the buildings to make them safe.”

A big focus on new buildings at the present time is sustainability.

Joe cited a buildings experts called Frank Mills as revealing that a lot of the skills and practices used to put measures in place for Covid could be transferred to help protect the environment.

Above all, he thinks the pandemic has helped usher in a more collaborative culture.

“I thought it brought the best out in people,” he added. “I found in our institution that people were coming together with a common cause.

“The mission of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers is improving the world through engineering. Seldom has that motto been more relevant and the thing that really impressed me was people from all these different industries and universities came together, finding the time – the world really did come together.”