ST Andrews University has commenced a study, Ecosystem-level importance of STructures as Artificial Reefs (EcoSTAR), in collaboration with an international team of experts to conclude what impact North Sea infrastructure has on marine life.

Speaking to Project Scotland, Dr Debbie Russell, senior research fellow at the university and principle investigator of the study, explained how wind turbines and oil rigs gradually become ‘artificial reefs’ with small plants and animals such as mussels attaching themselves to the structure and kickstarting the process.

An artificial reef is a man-made structure which either intentionally or unintentionally becomes home to marine species. Fish swimming in and around sunken ships is probably the most common image of an artificial reef.

“Even if the artificial reefs haven’t developed yet, there is often a rock dump at the bottom of wind turbines, for example, and that can act as hiding places for fish,” Dr Russell explained. “We did actually find that some individual seals forage at the foundations of wind farms that had been in the water less than six months.”

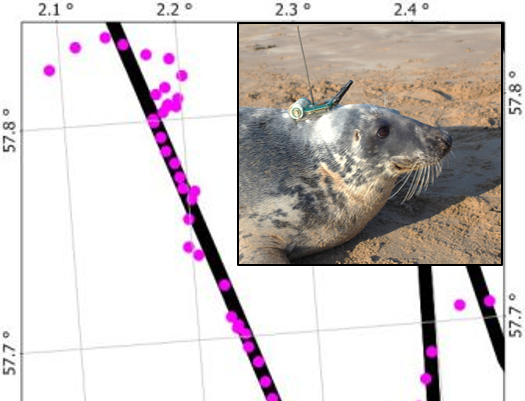

Specialising in marine mammals, Dr Russell’s previous research already resulted in seals having tracking devices attached to their fur (which fall off naturally once the seals begin their annual moult) to track their movements around the structures.

Although the EcoSTAR project, which is funded by the Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC) INfluence of man-made Structures In The Ecosystem (INSITE) programme, focuses on the impact of the structures on marine life, Dr Russell points out that there are other aspects that need be considered when policy decisions are made with regard to structure decommissioning and removal.

This includes the impact of the structures on commercial fishing activity, structure degradation and whether or not the sea should be returned to its pre-industrial state.

Dr Russell added, “I think marine life is certainly considered more now in the construction of North Sea infrastructure than it was historically, and especially with the development of wind farms. For example, the potential impact of construction on marine life is considered prior to developments, including how the loud noises may impact marine mammals during piledriving or the operation of wind turbines in terms of the potential impact on seabirds.

“There’s also increasing interest in the potential for structures to be engineered to maximise their potential as artificial reefs.”

Oil and gas firms are very much on board with the study, with the sector having already funded a previous stage of the project and also agreed to make data on their work available to researchers.

Dr Russell said that, should the findings establish that the infrastructure has an effect on a particular population of species then there could be scope to feed it into legislation, in terms of whether such structures should be removed once their operations are over, how marine life can be impacted and also if certain parts should remain in the ocean.

In America, some decommissioned oil rigs have been transported to state-approved ocean locations to be toppled over and naturally turned into artificial reefs. The initiative is called Rigs to Reefs.

Dr Russell explained that, although the Rigs to Reefs projects can be learnt from, their findings won’t directly translate into the different environment found in the cold North Sea. She said this is why the EcoSTAR project is so important – especially given that the North Sea, with all its infrastructure, presents considerations that by her own admission are not the area of expertise of ecologists.

It has been argued the Rigs to Reef programmes in America, Brunei and Malaysia are beneficial to fishermen. Fish are said to see the reefs as not only places to feed, but also safe havens – thus making them the prime spot for fishing, which would otherwise not be allowed if the rigs were in operation.

Dr Russell continued, “One of the key questions which is unanswered, is the so called attraction vs production debate, which is really about the degree to which structures concentrate animals that are already in the environment – so attract fish to congregate around them, which potentially makes these fish very vulnerable to marine mammals; or the degree to which these structures actually increase the production – so do they support an increase in marine life?

“The other thing to consider is that these structures are often associated with exclusion of other activities including commerical fishing and shipping.

“Because of the interaction between all the species, any impact on one level of the food chain can have a complex and sometimes counterintuitive impact on the rest of the food chain.”

EcoSTAR is a three-year project and the findings will at the very least give a better understanding of the highly industrialised North Sea and almost certainly shape its future.