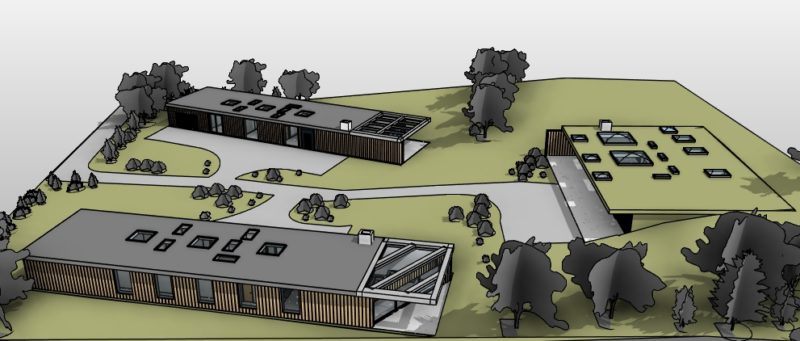

A planning application has been submitted for three carbon neutral homes in Aberdeenshire, which have been specified to the rigorous Passivhaus standard.

The dwellings are to be built in Cuminestown on redundant farmland, with the application achieving a platinum and gold sustainability label under section 7 of the building standards technical handbook, according to project architects Cooper & MacGregor.

Bob MacGregor, principal designer at the practice, told Project Scotland the client is the landowner, who is creating a nature walk on the surrounding land. It was the brief of creating three houses to complement this nature walk that led to the carbon neutral approach. The architect also had the Scottish Government’s aim of significantly reducing household and construction carbon emissions by 2020 in mind.

In order to meet the Passivhaus standard, the homes have been designed to incorporate a high level of insulation, insulated door and window frames, triple glazing and minimal opening windows, in a bid to retain heat.

Vestibule entrances have also been utilised to reduce heat loss through the main access and egress to the property, as well as the garage space, by “effectively creating a space that will take the hit in terms of the loss of heat before it enters the main body of the house,” Bob explained. “The garage is actually heated and insulated to the same standard as the houses, which again helps keep that level of heat and reduces the energy costs.”

Bob said a big consideration was the solar gains. He explained, “We used a drone survey to create a digital model of the site; it gave us pretty accurate levels but also the GPS coordinates so we could consider the path of the sun, so that’s really helped us maximise the solar gains to the property, and this also increases the natural light into the property as well.

“When we’re looking at the sustainability labels, this is really for achieving above and beyond the basic requirements and the building regulations under section 7 of the domestic regulations, so to achieve the platinum and gold sustainability levels we have to look at far higher levels of energy and water efficiency, reducing carbon emissions. A big thing now as well is the flexibility in design, and that’s really about future-proofing the building.” To aid flexibility, Bob said the things taken into consideration include space for home working, heated garages, and ease of accessibility and adaptability of the space.

“That’s a big problem if you look at some of the adaptations that are having to be made to older housing, particularly if people get ill or injured and they maybe need a wheelchair, or as they get older and their mobility reduces. People are spending quite large sums of money – and councils as well – subsidising alterations to these houses because they were never built in the first place to take that into consideration.

“Because you’re looking at a higher level for the sustainability labelling, accessibility and general quality of life – that focus means that long-term, it’ll massively reduce the cost because you shouldn’t really have to alter the property.”

The Passivhaus Trust claims that a Passivhaus design can reduce energy bills by 75%, Bob said.

“You’ve got much lower bills, which is a big thing for clients and I think that’s really what’s been the driving force behind a greater focus on sustainable design. Money talks, effectively, and that’s what clients are focused on, especially if the actual build might cost them slightly more than if you did it to the basic standard of housebuilding. If they can see that being offset over three to five years with energy costs, that’s really where the value in this build comes in.”

Bob said there had been a “growing interest” in Passivhaus in recent years, driven by potential savings, emerging technology and the Government’s drive to lower carbon emissions. This has, in turn, seen manufacturers focus on improving product efficiency.

“We noticed from doing the SAP calculations (that) 140ml of rigid insulation today offers far better efficiency than it did ten years ago, so there’s almost a natural increase led by customer demand that the manufacturers are continually improving. So even if you keep your specification the same, because that’s constantly improving in the background, you will always have improved thermal efficiency.”

Bob added that sustainable design has a “huge role to play” in future because architecture needs to address climate change, dwindling resources and a need to reduce emissions. “The industry is always moving toward greater energy efficiency. Manufacturers improve the efficiency of their products – insulation, windows, doors – and from a design perspective, building information modelling (BIM) is a massive advantage to sustainable design. You can carry out very, very realistic sun traces to look at the best positioning for glazing, for PV panels, whatever it might be; that’s absolutely brilliant for building orientation to maximise all the passive gains.”

Bob believes in future it will make economic sense to build sustainably due to the availability of technology and the evidence of both long and short-term benefits.

“Hopefully (we will) start to see an even greater focus on passive or energy efficient design within social housing because I think that’s where there will be a massive difference and a massive shift in attitudes, and if we start seeing the actual costs starting to drop then we can really push forward with it.”